The Last Time Intel Tried to Make a Graphics Card

Volition history repeat itself? Intel's setting out to brand a proper name for itself in the detached GPU space with its upcoming Xe-HP GPU lineup. We expect at Project Larrabee - the terminal time Intel tried making a graphics card - to understand how things might plow out.

AMD just took the CPU functioning crown, new consoles look similar minimalist PCs, and Intel's working on a flagship GPU based on the Xe compages, set up to compete with Ampere and Big Navi. 2022 has been a topsy-turvy year for a whole lot of reasons. Merely even so, an Intel graphics card? Yous'd be forgiven for chalking information technology off as yet another 2022 oddity, but that's where things get interesting.

Raja Koduri's baap of all isn't actually Intel's first attempt at a desktop-form detached GPU. 14 years ago, the CPU maker started work on Project Larrabee, a CPU/GPU hybrid solution touted to revolutionize graphics processing. Larrabee terrified the contest to the point that AMD and Nvidia briefly considered a merger.

What happened then? Three years of development, an infamous IDX demo, and and then… null. Project Larrabee quietly shuffled off stage, and some of its IP was salvaged for Xeon Phi, a many-core accelerator for HPC and enterprise workloads. Intel went dorsum to integrating small-scale, low-contour iGPUs with its processors.

What happened to Larrabee? What went wrong? And why haven't we seen a competitive Intel GPU in over a decade? With the Xe HP discrete GPU ready to launch adjacent year, we're looking today at the terminal time Intel tried to build a graphics card.

Intel Larrabee: What Was Information technology?

While Intel started piece of work on Project Larrabee quondam in 2006, the get-go official tidbit came at the Intel Developer Forum (IDF) 2007 in Beijing. VMWare CEO Pat Gelsinger, then a Senior VP at Intel, had this to say:

"Intel has begun planning products based on a highly parallel, IA-based programmable architecture codenamed "Larrabee." It will exist hands programmable using many existing software tools, and designed to calibration to trillions of floating point operations per second (Teraflops) of performance. The Larrabee architecture will include enhancements to accelerate applications such as scientific computing, recognition, mining, synthesis, visualization, financial analytics and health applications."

A highly parallel, programmable architecture, capable of scaling to teraflops of functioning. Gelsinger'south statement would've been a perfect description of any Nvidia or AMD GPU on the market, except for i cardinal indicate: Larrabee was programmable and IA (x86)-based.

This meant that its cores were functionally like to full general-purpose Intel CPU cores, different the fixed-office shader units found in GPUs. Larrabee rendered graphics, just it wasn't a GPU in the conventional sense. To understand exactly how Larrabee worked, it'due south a good thought to beginning await at how conventional GPUs operate.

A GPU, a CPU, or Something Else? How Larrabee Worked

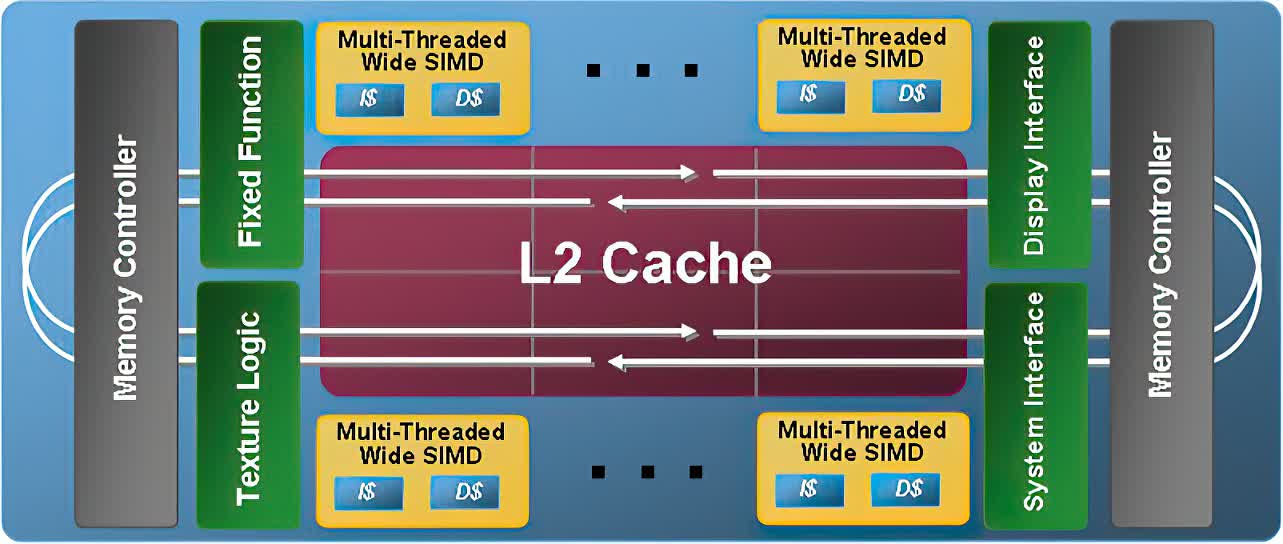

Nvidia and AMD GPUs are massively parallel processors with hundreds (or thousands) of very simple cores that handle stock-still-function logic. These cores are limited in terms of what they can do, but parallelization massively speeds up those particular graphics workloads.

GPUs are very skilful at rendering graphics. But the fixed function nature of their shader cores made it hard to run non-gaming workloads on them. This meant that game technology innovations were often held in check by graphics hardware capabilities.

New DirectX or OpenGL graphics feature sets required entirely new hardware designs. Tessellation, for example, is a DirectX eleven characteristic that dynamically increases the geometric complexity of on-screen objects. AMD and Nvidia needed to implement stock-still-function tessellation hardware into their Fermi and Terascale 2 cards to leverage this new adequacy.

Larrabee, in contrast, was built out of a large number of simplified x86-compliant CPU cores, loosely based on the Pentium MMX architecture. Dissimilar GPUs, CPUs feature programmable, general-purpose logic. They can handle just about whatever kind of workload with ease. This was meant to be Larrabee's big trump card. A general-purpose, programmable solution like Larrabee could practise tessellation (or any other graphics workload) in software. Larrabee lacked fixed function hardware for rasterization, interpolation, and pixel blending. In theory, this'd incur a operation penalization. Even so, Larrabee'southward raw throughput, the flexibility of those x86 cores, and Intel's promised game-specific drivers were meant to make up for this.

Developers wouldn't exist limited by what functions graphics hardware could or couldn't perform, opening the door to all kinds of innovation. In theory, at least, Larrabee offered the flexibility of a many-core CPU, but with Teraflop-level raw throughput that matched top 2007 GPUs. In practice, all the same, Larrabee failed to deliver. Higher-cadre configurations scaled poorly. They struggled to match, permit alone beat AMD and Nvidia GPUs in conventional raster workloads. What exactly led Intel downwardly this technological dead-finish?

Costs and Philosophy: The Rationale Behind Larrabee

Corporations like Intel don't invest billions of dollars towards new paradigms without a long-term strategic goal in mind. By the mid-2000s, GPUs were gradually condign more flexible. ATI debuted a unified shader architecture with the Xbox 360's Xenos GPU. Terascale and Tesla (the Nvidia GeForce 200 series) brought unified shaders to the PC space. GPUs were getting amend at generalized compute workloads, and this concerned Intel and other chip makers. Were GPUs about to brand CPUs redundant? What could be done to stalk the tide? Many chipmakers looked to multi-core, simplified CPUs as a way forward.

The PlayStation 3's Jail cell processor is the best-known outcome of this line of thought. Sony engineers initially believed that the 8-core Cell would be powerful enough to handle CPU and graphics workloads all by itself. Sony realized its error belatedly into the PlayStation three'south development bike, tacking on the RSX, a GPU based on Nvidia's GeForce 7800 GTX. Most PlayStation 3 games relied heavily on the RSX for graphics workloads, often resulting in worse performance and epitome quality compared to the Xbox 360.

Cell'due south SPUs (synergistic processing units) were used by some first-party studios to help with graphics rendering -- notably in Naughty Canis familiaris titles like The Concluding of Us and Uncharted 3. Cell certainly helped, simply information technology conspicuously wasn't fast enough to handle graphics rendering on its ain.

Intel idea along similar lines with Larrabee. Unlike Cell, Larrabee could scale to 24 or 32-core designs. Intel believed that the raw amount of processing grunt would let Larrabee compete effectively with fixed-function GPU hardware.

Intel'southward graphics philosophy wasn't the deciding gene, though. It was cost. Designing a GPU from scratch is extremely complicated, time-consuming, and expensive. An all-new GPU would take years to design and cost Intel several billion dollars. Worse, there was no guarantee that it'd beat or fifty-fifty lucifer upcoming Nvidia and AMD GPU designs.

Larrabee, in contrast, repurposed Intel's existing Pentium MMX architecture, shrunk down to the 45nm process node. Reusing a known hardware blueprint meant Intel could (in theory) become a working Larrabee design out on the market faster. It would also brand it easier to set up and monitor operation expectations. Larrabee ended up called-for a several-billion-dollar hole in Intel's pockets. Even so, cost-effectiveness was, ironically, one of its initial selling points. Larrabee looked revolutionary on paper. Why did it never take off?

What Went Wrong with Larrabee?

Larrabee was a nifty thought. Only execution matters just as much equally innovation. This is where Intel failed. Throughout its iv-yr lifecycle, Larrabee was plagued by miscommunication, a rushed development cycle, and fundamental bug with its architecture. In retrospect, there were cherry-red flags correct from the beginning.

Gaming wasn't even mentioned every bit a use case in Larrabee'southward initial announcement. However, almost immediately later on, Intel started talking about Larrabee'due south gaming capabilities, setting expectations heaven-high. In 2007, Intel was several times larger than Nvidia and AMD put together. When Intel claimed Larrabee was faster than existing GPUs, information technology was taken as a given, because their talent pool and resource budget.

Larrabee gaming expectations were hyped even further when Intel purchased Outset Software, months afterwards buying the Havok physics engine. The studio's kickoff game, Projection Start, was demoed in 2007 and showcased unprecedented visuals. Unfortunately, nothing came out of the Commencement Software buy. Intel shuttered the studio in 2022, around the fourth dimension it put Larrabee on agree.

Intel's gaming functioning estimates ran counter to the hype. A 1GHz Larrabee blueprint, with somewhere between 8 to 25 cores, could run 2005'due south F.E.A.R. at 1600x1200 at 60 FPS. This wasn't impressive, even by 2007 standards. By estimating Larrabee's operation at 1GHz, instead of the expected shipping frequency, Intel undersold the part's gaming capabilities. In a PC Pro article, an Nvidia engineer scoffed that a 2022 Larrabee card would deliver 2006 levels of GPU performance.

Who was Larrabee for? What was it good at doing? How did it stack upwards to the competition? The lack of clarity on Intel's part meant that none of these questions were ever answered. Communication wasn't the but issue, however. As development was underway, Intel engineers discovered that Larrabee had serious architectural and design bug.

The GPU that Couldn't Scale

Each Larrabee core was based on a tweaked version of the depression-performance Pentium MMX compages. Per-cadre operation was a fraction of Intel'southward Core 2 parts. However, Larrabee was supposed to make up for this by scaling to 32 cores or more. It was these big Larrabee implementations -- with 24 and 32 cores -- that Intel compared to Nvidia and AMD GPUs.

The problem here was getting the cores to talk to each other and work efficiently together. Intel opted to utilise a band jitney to connect Larrabee cores to each other and to the GDDR5 memory controller. This was a dual 512-scrap interconnect with over i TB/s of bandwidth. Thanks to cache coherency and a surfeit of bandwidth, Larrabee scaled reasonably well… until you hit 16 cores.

One of the key drawbacks to the ring topology is that data needs to pass through each node on its way. The more than cores you take, the greater the filibuster. Caching can alleviate the issue, just but to a sure extent. Intel tried to solve this trouble by using multiple band buses in its larger Larrabee parts, each serving 8-xvi cores. Unfortunately, this added complexity to the design and did niggling to alleviate scaling issues.

Past 2009, Intel was in a catch-22: 16-cadre Larrabee designs were nowhere nigh as fast as competing Nvidia and AMD GPUs. 32 and 48-cadre designs could close the gap, simply at twice the power consumption and at an immense added cost.

IDF 2009 and Quake 4 Ray-Tracing: Shifting the Conversation

In September 2009, Intel showcased Larrabee running an actual game, with real-time ray-tracing enabled, no less. This was supposed to be Larrabee'due south watershed moment: in-development silicon running Quake 4 with ray-tracing enabled. Here was Larrabee hardware powering through a real-game with lighting tech that was merely not possible on GPU hardware at that time.

While the Quake four demo generated media buzz and stoked discussion well-nigh real-time ray-tracing in games, it skipped over far more serious issues. The Quake 4 ray-tracing demo wasn't a conventional DirectX or OpenGL raster workload. It was based on a software renderer that Intel had earlier showcased running on a Tigerton Xeon setup.

The IDF 2009 demo showed that Larrabee could run a complex piece of CPU code fairly well. But it did null to clear questions about Larrabee'south raster performance. By attempting to shift the chat away from Larrabee's rasterization performance, Intel inadvertently drew attention dorsum to it.

Simply three months after the IDF demo, Intel appear that Larrabee was beingness delayed and that the projection was getting downsized to a "software development team."

A few months subsequently, Intel pulled the plug entirely, stating that they "will not bring a detached graphics product to the market, at least in the short term." This was the end of Larrabee every bit a consumer production. However, the IP that the team built would go along in a new, enterprise avatar: the Xeon Phi.

Xeon Phi and the Enterprise Market: Coming Full Circle

The strangest part of the Larrabee saga is that Intel actually delivered on all of its initial promises. Dorsum in 2007, when Larrabee was starting time announced, Intel positioned it as a assuming, new offering for the enterprise and HPC markets: a highly-parallel, many-cadre, programmable design that could crunch numbers far faster than a conventional CPU.

In 2022, Intel announced its Xeon Phi coprocessor, designed to do exactly that. The first-generation Xeon Phi parts even came with PCIe out: information technology was a die-shrunk, optimized Larrabee in all simply proper name. Intel continued to sell Xeon Phi coprocessors to enterprise and research clients until last year, earlier quietly killing off the product line.

Today, with Intel working again on a detached GPU architecture, in that location are definitely lessons to exist learned hither, forth with hints near Intel'due south long-term strategy with Xe.

Learning from Larrabee: Where Does Xe Go From Hither?

Intel Xe is fundamentally dissimilar from Larrabee. For starters, Intel now has a lot of experience building and supporting modern GPUs. E'er since the HD 4000, Intel'south invested considerable resources towards building capable GPUs, supported by a fairly robust software stack.

Xe builds on top of over a decade'due south feel, and it shows. The Intel Xe-LP GPU in superlative-finish Tiger Lake configurations matches or beats entry-level detached GPUs from AMD and Nvidia. Xe manages this, fifty-fifty when it has to share 28W of power with four Tiger Lake CPU cores. Inconsistent performance across games indicates that Intel's commuter stack withal needs some piece of work. But more often than not, Xe-LP holds its own confronting entry-level AMD and Nvidia offerings. Xe (and previous-generation Intel iGPUs) make use of a number of Larrabee innovations, including tile-based rendering and variable SIMD width: the R&D Intel put towards Larrabee didn't go to waste material.

While Xe-LP proves that Intel can build a decent, efficient mobile graphics bit, the real question here is how Xe-HPG, the discrete desktop variant, will perform. Efficient, low-ability GPUs don't always scale upwards into 4K gaming flagships. If that were the case, Imagination's supremely efficient PowerVR chips would be giving Nvidia and AMD a run for their coin.

Based on what Intel's said then far, Xe-HPG should offer feature parity with modern AMD and Nvidia GPUs. This means hardware ray-tracing and full support for other aspects of the DirectX 12 Ultimate feature-set. Intel also talked about using MCM to scale performance on upcoming Xe parts. By packing multiple GPU dies on a single MCM package, future Xe designs could scale operation well beyond what nosotros're seeing with Ampere and Large Navi today.

However, the competition isn't standing nevertheless. AMD'southward already leveraging MCM in its chiplet-based Zen CPU design, while Nvidia'south side by side-generation "Hopper" GPUs are too expected to utilise the engineering to maximize performance.

The question, so, isn't really whether or not Intel can build a great detached GPU -- it probably can. But in a apace evolving hardware space, what matters is how Xe-HPG will stack up against upcoming Nvidia and AMD GPUs.

Intel has lessons to acquire here from Larrabee: clear communication and expectation management are disquisitional. Moreover, Intel needs to evolve and stick to realistic development timelines. A two-year wait could set Xe back a generation or more. And lastly, they need to focus on developing a mature driver stack: a powerful Xe-HP GPU won't count for much if it'due south held back past spotty drivers.

Is Xe going to usher in a new era of Intel graphics authorization? Or will it go the way of Larrabee? We'll only know for sure in the months to come when the "baap of all" makes it to market.

Keep Reading. Hardware at TechSpot

- The Ascension, Fall and Revival of AMD

- Ryzen 5 3600 + RTX 3080: Killer Combo or Not?

- How CPUs are Designed and Built

- Explainer: What Are Tensor Cores?

Source: https://www.techspot.com/article/2125-intel-last-graphics-card/

Posted by: martineztorandready.blogspot.com

0 Response to "The Last Time Intel Tried to Make a Graphics Card"

Post a Comment